Capital & Main generated this story. Permission is granted for its publication here.

An oil corporation will be mostly responsible for providing a thorough accounting of the ground’s degradation as one of the most contaminated areas of Los Angeles County is shortly to be cleared for new development.

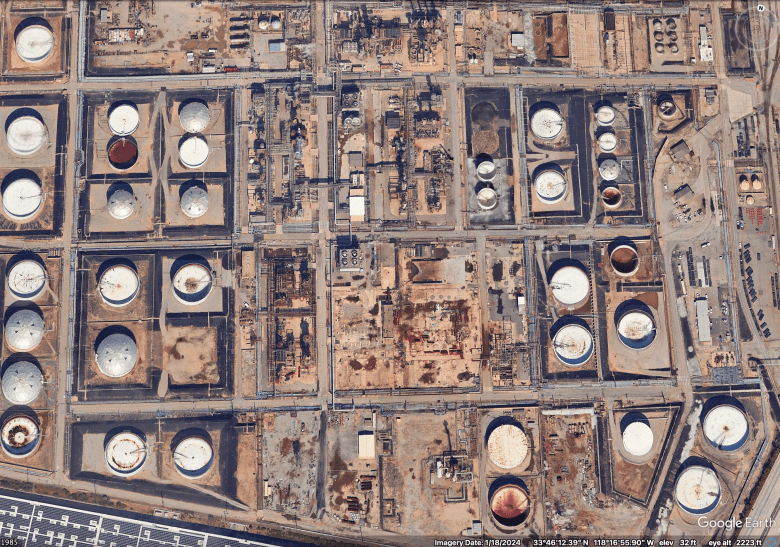

Truckloads of slop oil and acid sludge were buried on-site by employees of an oil refinery with related facilities in the Wilmington area and neighboring city of Carson for about 40 years in the middle of the 20th century. According to state data, a large portion of that garbage is still present in the soil and water table decades later.

By year’s end, the century-old refinery, currently owned by Phillips 66, will shut down its operations. The contaminated subsurface layer might be almost 16 feet deep in certain places. However, Phillips 66, which attributed its closure to market forces, is the only source of estimates for the expense of demolishing the refinery and cleaning up the contaminated area.

According to Ann Alexander, a principal at Devonshire Strategies and an environmental policy analyst, the lack of a disclosure requirement regarding the true cost is a major issue. She stated that there is now an underground lake of hydrocarbons because of the amount of garbage that has collected beneath and around the refinery. Decades may pass before it is resolved.

The refinery, which can generate up to 139,000 barrels of oil products per day, has raised concerns among community groups that Phillips 66 will transfer the financial and health costs to the general population. A representative for the company stated that it is creating plans to keep clearing toxic soil, but the corporation declined to comment.

In an email, spokeswoman Al Ortiz stated, “We are in the preliminary planning stages for this work and cannot speculate on a definitive timeline or estimated cost of the decommissioning and remediation.”

Major oil refineries closing is uncommon, but it might happen more frequently as state and local governments shift to renewable energy sources, as California intends to do by providing subsidies for electric cars.

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the shutdown of the Phillips 66 refinery and a refinery owned by Valero in the Bay Area city of Benicia next year will result in a slight increase in gas prices. While lawmakers debate whether to expedite refinery permit approvals, California officials are hoping that other businesses would purchase one or both of the refineries and continue to operate.

Regulators have been testing the groundwater for years, and the results show a poisonous legacy. Lead from buried waste and hazardous amounts of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from foam used to put out refinery fires are two of the contaminants found in the groundwater beneath the Carson and Wilmington facilities, which are regulated by the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board.

According to Danny Reible, an environmental engineering professor at Texas Tech University who has counseled governments on such cleanups, none of them break down naturally and will probably need to be held underground. According to Reible, eliminating all of this pollution is practically difficult.

Certain pollutants have seeped into drinking water sources, such as aquifers. Since 2023, a groundwater monitoring well in a community around half a mile from the Wilmington site has had excessive levels of tert-butyl alcohol, a gasoline additive, in more than five different samplings by Phillips 66.

Since 2008, when officials feared pollution had moved to the area, the well—which is not used for drinking water—has been examined because it touches an aquifer that is connected to drinking water wells in South L.A. The Los Angeles water board stated that it did not test drinking water wells for the pollutant because they are all more than a mile away from the refinery, and Phillips 66 stated that the refinery is not responsible for the tert-butyl alcohol discoveries.

After this report was published, a representative for the Los Angeles water board stated that the closest active drinking water well is about 1.5 miles northeast of the refinery, and the most recent sampling data from that well did not reveal tert-butyl alcohol.

According to two 2005 reports—one from the local water board and one from the U.S. EPA—the Carson site’s contamination of the Silverado aquifer may have an impact on neighboring drinking water wells.Tert-butyl alcohol was discovered in a groundwater monitoring well at the refinery during sampling last year.

According to the Phillips 66 spokeswoman, the contaminated water is being pumped and sent to recycling facilities and disposal sites. According to the Los Angeles Water Board, 317 million gallons of contaminated groundwater, equivalent to 480 Olympic pools, and 2.8 million gallons of light non-aqueous phase liquid—a coating of petroleum contamination that floats on top of water—have been removed. In order to break down certain pollutants, a device called a biosprage system additionally introduces pressured air into the contaminated layer.

According to tests conducted last year, there is a plume of volatile organic compounds in the soil above the groundwater, including the recognized carcinogen benzene and other gasoline constituents including diisopropyl ether and methyl-tert-butyl ether. Their poisonous fumes can enter buildings and ascend.

Catellus Development Corporation and Deca Companies were hired by Phillips 66saidit to assess the 650-acre refinery facility, which is roughly the size of 500 football fields. Requests for interviews were not answered by either.

Following refinery closure, regulators have a restricted and perhaps ambiguous role.

According to spokesperson Jackie Carpenter, the water board will keep testing groundwater but is not involved in the shutdown. Phillips 66 might be subject to sanctions, which it hasn’t done recently.

Capital & Main was informed by the Department of Toxic Substances Control that it solely manages the removal of trash from a stormwater holding basin coated with concrete at the Wilmington location and an asphalt-capped pond at the Carson plant. For tracking purposes, any future garbage that is deemed hazardous would also need to be reported.

Crude oil is refined into petroleum products at the Phillips 66 refinery complex in Carson.

Governor Gavin Newsom’s press office did not respond to a request for comment.

According to U.S. EPA spokesman Julia Giarmoleo, states have the authority to control groundwater contamination and solid waste. (In 2019, the EPA rejected the criteria for oil refineries to be superfund financially responsible.)

Environmental justice groups are pressuring the state of California to implement a refinery wind-down procedure, but they are concerned about a lack of cooperation.

According to Sylvia Arredondo, director of citizen engagement at Communities for a Better Environment, the process has been chaotic. Rather, the state ought to take the initiative to implement it gradually.

And the prices are unknown.

According to Phillips 66’s filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission, the cost of asbestos removal and asset decommissioning at its refinery in Los Angeles would be $231 million.

However, according to Faraz Rizvi, policy and campaign manager for Asian Pacific Environmental Network, which is hosting a town hall meeting to get feedback from locals, decommissioning and cleaning are two distinct processes with drastically different price tags.

Refinery owners are permitted to assume that refineries have no retirement date, and their disclosure of those expenses is largely unregulated. In contrast, other industries, including nuclear, have more set retirement dates and require plant owners to keep a fund to close generating units.

Get neighborhood news in your inbox. It’s free and enlightening.

Become one of the 20,000+ individuals who receive breaking news alerts and the Times of San Diego in their inbox every day at 8 a.m.

Weekly updates from San Diego communities have also been provided! You acknowledge and agree to the terms by clicking “Sign Up.” Choose from the options below.

According to the London-based think tank Carbon Tracker, which based its estimates on daily output capacity, the actual closure costs of six of the biggest oil refining companies in the United States, including Phillips 66, are estimated to be $34 billion combined, but their own estimates come to less than $1 billion.

Taxpayers could end up covering shortfalls, said Eric Stevenson, a former director of meteorology, measurement and rules at the Bay Area Air Quality Management District. According to Stevenson, it’s the Wild West at the moment.

In 2024, Phillips 66 recorded a refinery loss of $908 million in Los Angeles. Its leadership saw a shakeup after the hedge fund led by billionaire Paul Singer bought $2.5 billion stake in the company and pushed for a focus on other assets, including a petroleum export hub near Houston.

Mass layoffs have followed Singer s involvement at other companies, such as a petroleumrefineryin Contra Costa County owned by Marathon Petroleum. About 600 employees and 300 contractors work at the Los Angeles refinery.

Phillips 66 will retain a presence in Los Angeles. In addition to importing gasoline from its Washington state refinery, it faces federalchargesfor dumping 790,000 gallons of oil-laden wastewater into county sewers in 2020 and 2021. A criminal trial is scheduled for next year.

Standing outside the Wilmington refinery on a recent morning, longtime resident Anita Gomez urged a group of staff members for state lawmakers not to let the company skirt its obligations.

She said action is needed to prevent repeating what has happened at other shuttered industrial facilities in the area, including a battery recycling plant in Vernon, where industries havewalked awayand left the cleanup of their pollution to taxpayers.

They simply close and don t clean up, Gomez said.

Capital & Mainis an award-winning nonprofit publication that reports from California on the most pressing economic, environmental and social issues of our time, including economic inequality, climate change, health care, threats to democracy, hate and extremism and immigration.

Copyright 2025 Capital & Main

by

by